Seeland

A Solo Reindeer Hunt in Norway

"The sense of having taken a life goes hand in hand with respect for the animal itself."

It was on day three of the hunt that I got the animal. I had used the morning gloom and mist to reach the top unseen. This was where I had spotted the deer on the first day, from where they then disappeared without a trace.

The 8 km hike up the mountain with a 30 kg pack was manageable, but my legs were feeling the 42 km I had covered in the previous two days and my thoughts were filled with the usual misgivings: what am I doing here?

Why put yourself through the fatigue, exhaustion, time away from the family, the risk of returning home empty-handed – all for some meat and perhaps a trophy?

I can’t answer this question – but if you're reading this, I’m sure you know what I’m talking about.

Sooner or later, the mist always lifts. Pain and fatigue fade – but memories and a potential trophy endure. So I made my way upwards.

At around ten, the mist finally lifted. While waiting for this moment, I had put on all my clothes. Cold is no friend to the hunter. Long underwear, fleece, down jacket, and waterproof and windproof outer. Beanie pulled down over the cap, with the jacket hood as a crowning touch. I had spent the last two hours making coffee, while scanning the mountainsides that briefly emerged from, and were as quickly subsumed in, dense mist.

Once the mist dispersed, it was as though it had never been there. Everything was as clear and beautiful as only a late-August Norwegian mountainside can be. The strong wind alone was a reminder that Mother Nature was still the gatekeeper for these mountains.

I removed all my warm clothing. I was going to start hiking and it’s crucial not to get sweaty. Outerwear protects from the wind, and heat from the body escapes through the vents under the arms and down the legs.

A couple of hundred metres to the top and another valley with stunning views appears. The barren landscape with large rocks, lichen, blueberries, and little shrubs that want to grasp at your tired ankles and trip you into the nearest stream.

The trees are 1,000 metres below, indistinct little green sticks surrounding the multitude of lakes. There MUST be reindeer here.

The previous day, I had found the group again – but right down by the lakes. There had been 4 kilometres to descend, and three hours before sunset was not a time to start hunting.

If – and only if – you’re lucky enough to get a shot in, it takes 2 hours on a good day to break, skin, dismember and completely debone a reindeer. Then it has to be carried down off the mountain. Meaning, in this particular case, first 6 kilometres uphill. Then 10 kilometres down. Twice over. For most of us, carrying a pack, tent, rifle, binoculars, food PLUS the 50kg of meat and head of an adult reindeer all in one go is not an option. It takes two trips.

The wind was perfect. From the top, the ridge split into two. I picked the direction where I had seen them the day before.

There they were!

After 500 metres, I spotted a group of deer grazing 600 metres further down.

It was them – the same group I had seen on the two previous days – but now they were within range.

As with other large deer, males often collect in bachelor groups before the rut in order to pit their mighty antlers against each other, like mortal enemies, when the battle for mating rights begins in September.

I take the rifle from the rucksack, load it and secure it. The rucksack then goes back on and I take a wide detour to remain unseen by the quarry. They are totally calm and completely unaware of my presence. All the same, my heart is beating and my mouth is dry. Not from the physical exertion, but from the thrill of imminent success in a pursuit I love.

I scan down the mountainside and in a good wind I climb the rock that is exactly opposite where I last saw the animals. I put my rucksack down and mark the spot on the GPS. Countless people have wasted hours searching for a rucksack they thought they could ‘easily find again’. With my trusty Sauer 202 .308W calibre in one hand and my cameras in the other, I crawl to the edge and peer over.

The deer have moved a little further away and I have to break cover to approach them. In this strong wind, a shot over 100 metres is not safe. I creep backwards behind a rock and advance 30 metres unseen. An alert reindeer spots me, and in a matter of moments he has relayed his concerns to the others – and they’re gone. Once more.

At 90 metres’ distance, I settle down on the edge. The deer are restless now. When they sense danger, they clump together, and a legitimate shot is impossible.

Two to the left of the group are superb bucks, and as soon as one of them is clear of his surroundings, a suppressed shot sounds out in the mountains.

The buck is clearly hit and starts running. He manages just a few metres before my second shot hits home. With no schweisshund to track a blood trail, it is crucial to stop the deer running down into another valley, which would involve an even longer retrieval.

With a third cartridge chambered, I quickly run towards the animal that has disappeared behind a rock. The beautiful buck lies peaceful and still, 30 metres from the first shot. Vanquished but majestic.

The emotion is overwhelming. From thoughts of failure to the ecstasy of a task accomplished. The sense of having taken a life goes hand in hand with respect for the animal itself. One that has demanded such mental and physical commitment, provided meat for the whole winter and a beautiful set of antlers to remind me of the mountains on that windy August day.

It’s only 13.30. Sunset is at 20.40, so there’s plenty of time to deal with the buck. Or is there?

With several people on the job or the facilities of an abattoir, the task would be much easier. To save weight, I don’t carry a large knife but rather a lightweight scalpel-like knife with replaceable blades.

With the animal on its side, I open the throat in the usual way and the windpipe and foodpipe are separated above the breastbone.

I open the abdomen and diaphragm so that the heart, lungs, windpipe and foodpipe can be drawn out. I cut open the pelvis to pull the rectum out together with the other major internal organs.

I skin the animal while it’s lying on its side, removing the leg and shoulder. The sirloin and the meat on the massive neck and pelvis are removed. The belly and rib meat – and of course the tenderloin. I then turn the animal over and repeat on the other side.

I bone the leg and shoulder. The weight has to be minimised as much as possible. The meat is put into cotton bags and then in a large plastic bag. The head with its magnificent antlers is cleaned of skin and meat, and the mandatory brain and lymph node samples are taken and labelled.

And then I’m ready – for the first trip. On the 1,200-metre climb, I have a broad smile on my face. Now and then I have to turn around and check out the carcass, where the ravens are already busy playing their role in the circle of life. It’s no longer just a dream – I actually got my reindeer. From the summit, there are 8 kilometres downhill to my car. With the rucksack emptied to the bare minimum, up I go again. I load 30kg of meat and finally strap the antlers on.

It’s just before sunset when I descend for the second time to my car parked on the mountain track. I pitch my tent and devour the incredibly tasty freeze-dried pasta carbonara with an ice-cold beer before collapsing exhausted into a deep sleep with sweet dreams of reindeer and Norwegian mountains.

Gear - What to take and why

I recently returned from my fourth reindeer hunt in Norway with my biggest reindeer yet. An amazing animal but, as always, an incredibly tough hunt – physically and emotionally. A hunt in stunningly beautiful surroundings – but which can also be very harsh and even dangerous. Reindeer hunting is hunting in its purest form.

Depending on where you hunt, you can opt to walk up into the mountains from a car park each day or, like me, take a week’s supplies in your rucksack and head off. Below, I’ve divided the things you need to take into three groups: clothing – gear – contingencies.

Clothing

On these hunts, clothing is a critical factor.

I was hunting at between 900 to 1,200 metres from late August to late September. This means you might be climbing with 40kg on your back in 25⁰C but have freezing temperatures in the tent at night. So how do you prepare for every eventuality without overburdening yourself?

Shell layer

One essential item is a windproof and waterproof shell with a breathable membrane. Check the zips – they need to close and stay closed reliably, and ideally have windproof and waterproof covers. The jacket needs a hood for when the wind blows hard – and believe me, it often does. Zipped vents under the arms and down the legs will prove necessary when you are carrying out 30kg of meat and a trophy. People have different preferences, but nobody I know would take a lined jacket. Layering is the way forward to adapt perfectly to the temperature.

Down jacket

Bury me in a down jacket! What could be better! They compress down to nothing. They are nearly weightless but provide tremendous insulation as a mid-layer. I wear mine when sitting scanning for animals with my binoculars, at dinner in the evening, with my morning coffee, and in my sleeping bag at night, which saves me the weight of a heavy bag.

Long underwear

A must – no question about it. Long underwear makes for a comfortable base layer that weighs nothing. Go for Merino wool, with the possible addition of a stretchy fibre. It has countless benefits. It insulates brilliantly, even when wet. It dries quickly, and has superb sweat-wicking capabilities.

Moisture-wicking T-shirt

When I set out on a warm, late-summer day, I wear a moisture-wicking T-shirt. They weigh next to nothing and provide a nice extra layer for a bit of warmth. But avoid cotton. It dries slowly, makes you cold when you sweat and quickly starts smelling like a school changing room.

Rainwear

If you have proper waterproof clothing, an extra rainproof outer is not needed. But a lightweight set of rainwear is easy to carry and provides extra security – best to be prepared (see Emergencies below).

Boots

Again, people’s preferences vary. Some could run a marathon in wellingtons. My recommendation is a pair of hiking boots. Do not use the hunt to break in new boots. Whether to choose membrane or full leather is probably a matter of taste, waterproofness isn’t. Membrane boots are good at staying dry, but are slow to dry when wet. Leather boots dry more quickly.

Hat and gloves

It can turn cold fast, so bring a good beanie – for night-time wear too. A cap for protection from the sun and to hide the glare of your face from the deer. I find that thin work gloves function sufficiently. But for hunting later in the season, warmer and, especially, waterproof gloves are essential.

Tent, sleeping bag and sleeping mat

I hunt alone and use a 2-person lightweight tent that comes in at 950 grams. It’s decidedly too small for two people, but suits one person with a pack. A good tent is essential. In bad weather, you could find yourself in it for 24 hours straight. I use a relatively lightweight sleeping bag, even in night-time sub-zero temperatures. I sleep in my clothes for warmth and to save a lot of weight. A lightweight inflatable sleeping mat does the business. It insulates and is comfortable!

Trekking poles

The 70-year-old Norwegian who introduced me to reindeer hunting thought that trekking poles were for old people. Despite poor vision in one eye and a less than steady hand, he sees the reindeer before me and has shot more than I ever will. He would never dream of using trekking poles, but I am all for them... They provide extra balance on uneven ground and take strain off the knees when descending. A pair of carbon poles could be in the hundreds of dollars – but they’re worth the money!

Rifle and ammunition

I use my trusty Sauer 202 fitted with a ZEISS 3-12x56 scope with a ballistic turret. I’ve shot reindeer at between 90 and 340 metres and, in these situations, understanding your ballistics is crucial. I shoot a Sako Powerhead Blade 10.5 gram.

My choice of calibre is .308w but any calibre suitable for larger deer is fine. Of course, you need to be comfortable using your weapon.

Electronics and optics

Hunting radio

When in groups, a hunting radio makes a lot of sense. You can cover a larger area and support each other. Check beforehand that its use is permitted.

Binoculars and rangefinder

You can’t do without good quality binoculars.

Reindeer are on the move around the clock, not only at dawn and dusk. So the key feature is not so much light sensitivity as anti-fogging. 10x magnification is a good choice since it allows you to cover a larger area. I also have a spotting scope with 60x magnification – but I never take it, as its power-weight ratio doesn’t hit the mark. It’s just too heavy. However, I can attach my binoculars to my camera tripod to prevent arm ache. A special adapter is available to attach your mobile phone to the binoculars and film from afar and then zoom in to determine the sex and size of the reindeer, even from several kilometres away.

Judging distance in the mountains is difficult. There are no trees for scale and a cliff might be either large or small.

So a rangefinder, and a good one, is indispensable. A cheap golf rangefinder is no good in mist and it’s no use if it doesn’t work when the target is in full sun. I used to use a separate rangefinder and binoculars – but now high-quality 10x42 binoculars with a built-in rangefinder fit the bill to perfection!

Mobile phone

Today’s constant companion offers not only a pocketable top-quality camera but sometimes mobile coverage, enabling weather forecasts and contact with the outside world.

Finally, if you’re stuck in a stormbound tent for 16 hours, you can pass the time watching a few films or shows that you didn’t finish bingeing.

Maps and route finding

I make sure I have access to at least three different solutions:

1: I use the brilliant Norwegian app HVOR, which lets you download detailed maps with elevation contours, trails etc. Even offline, you can see your position by GPS on the map.

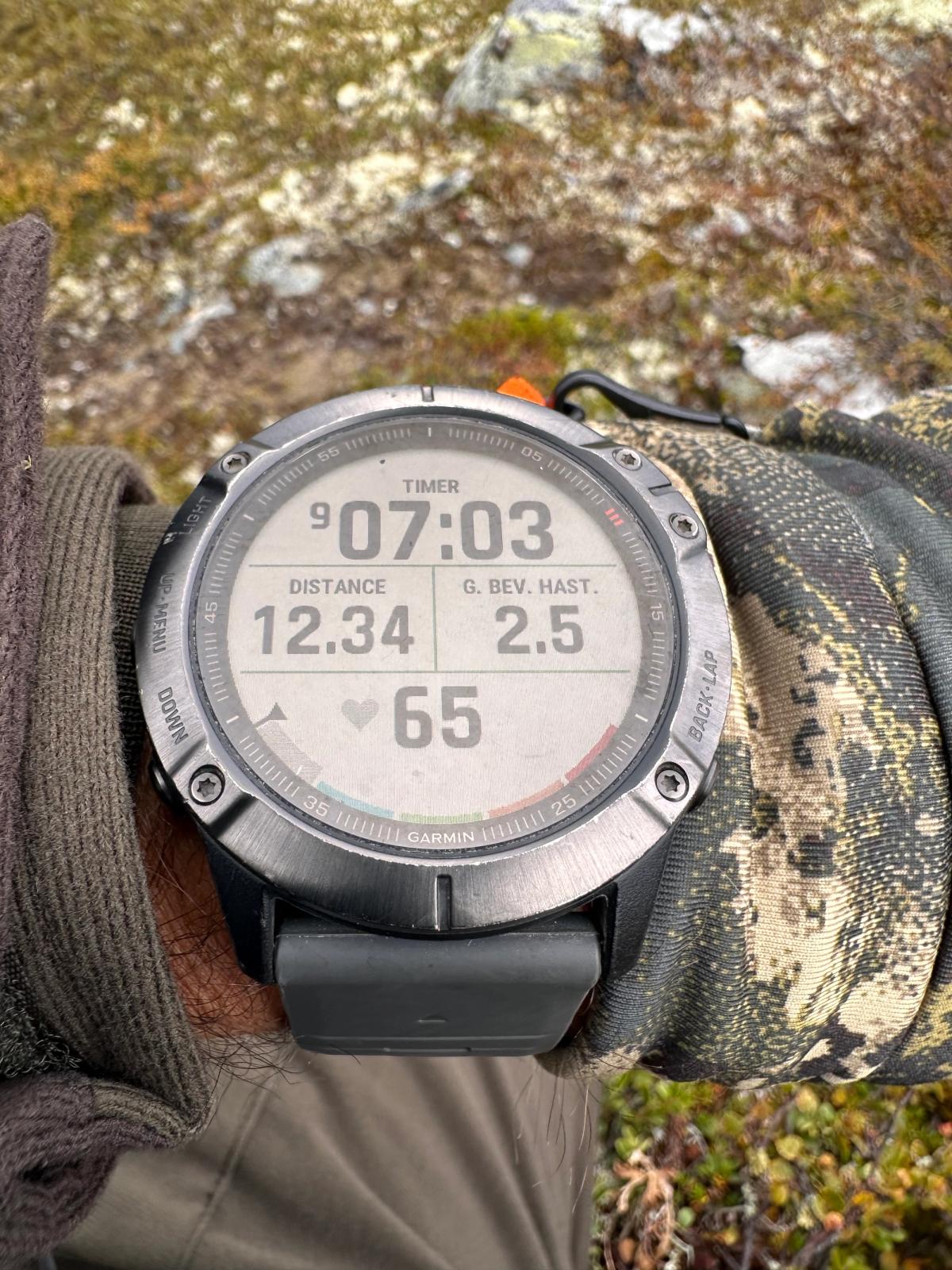

2: GPS. Standard handheld Garmin GPS that displays maps and position. You can drop a pin on your camp, track your route, where you left your rucksack, and much more. It really is a worthwhile investment. I once walked for 20 minutes right around my camp in the mist. It was marked by GPS, on my phone and my watch – but I couldn’t see it. Imagine if I hadn’t had a GPS...?

3: Regular map and compass. Remember them? They still work. Who doesn’t love a printed map? And they provide a secure analogue solution if all else fails.

Emergencies

Just like driving, flying and off-piste skiing, you need to pack things that you hope you’ll never need.

These contingencies can roughly be divided into three categories: electronics, gear and first aid.

Electronics

If you have no phone reception, run out of battery or lose your phone, you’re vulnerable in an emergency. That’s why I take the Garmin InReach mini with me; I hang it on my binoculars. It’s the first thing I put on in the morning and the last thing I take off at night. The InReach has an emergency button that sends a message by satellite to the emergency services. Some models also enable SOS messages and provide weather forecasts.

The Norwegian Rescue Services also have an emergency app "113" that works via satellite. This produces the same outcome as InReach – but you need battery life on your phone...

Gear

If you are injured, you have to be able to stay warm. So don’t leave your clothes behind in the tent. Many people rely on the legendary Norwegian multi-use “Fjellduk”, which has mountain camouflage on the outside and foil inside for warmth. It can also be converted into a tent, poncho and much else besides. Always carry extra food and water and never leave your rucksack too far away.

First aid

There are plenty of first aid kits available, many of them excellent. Check the contents to see if they match your needs.

Bleeding can be stanched by compression, so compresses are essential. I also take a suture kit for cuts, and, with a little imagination, serious outdoor wound treatment is perfectly possible.

Take painkillers and personal medication of course. Ordinary paracetamol and ibuprofen are excellent for sore muscles and will take the edge off more serious pain while you’re waiting to be rescued. Above all, familiarise yourself with what to do in an emergency. If you have trained for an emergency situation and evaluated the different scenarios, you will be better able to cope when faced with a genuine injury and a potentially hazardous situation.